Sold Out

What is a Complex Early Seral Forest

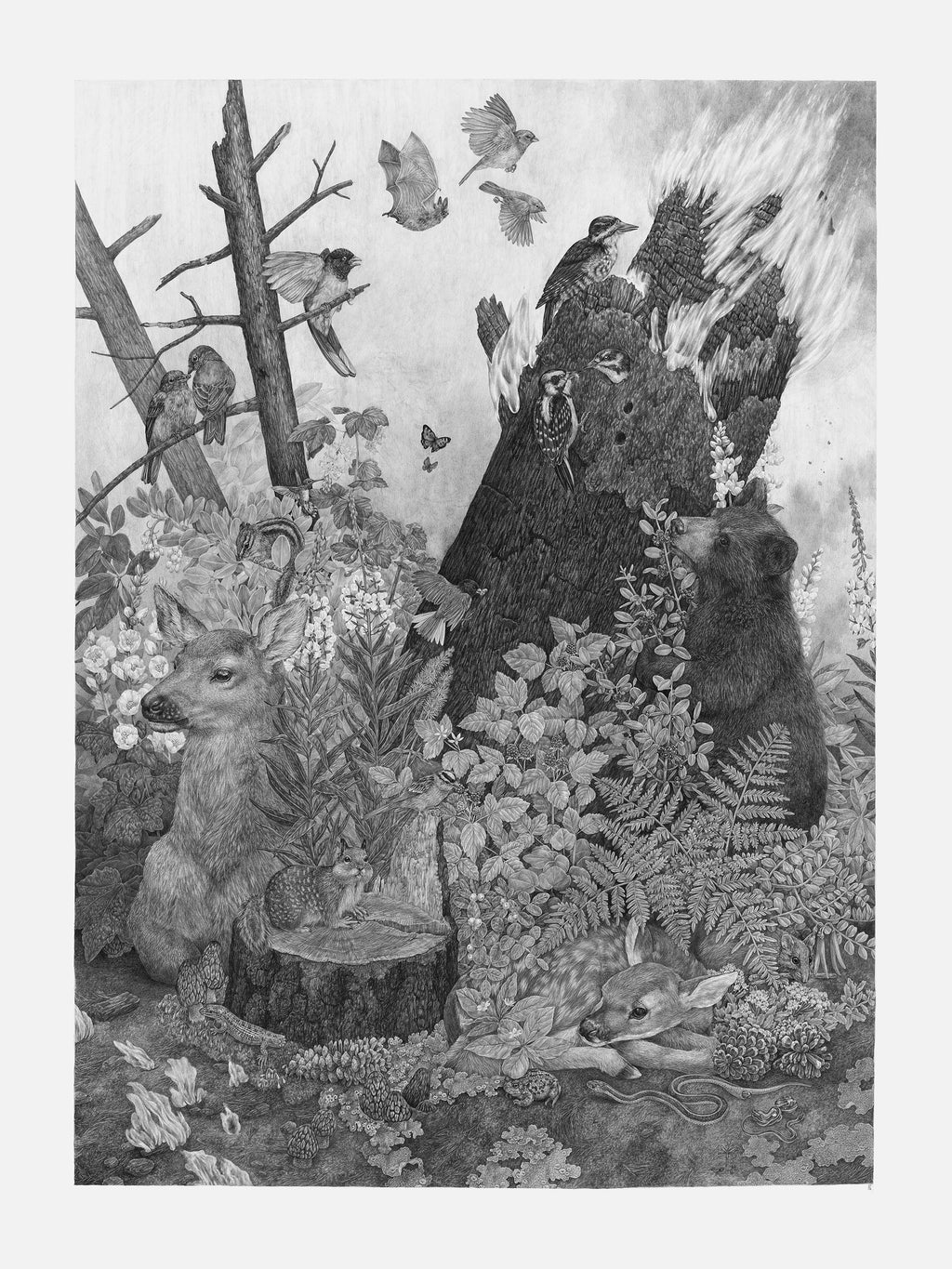

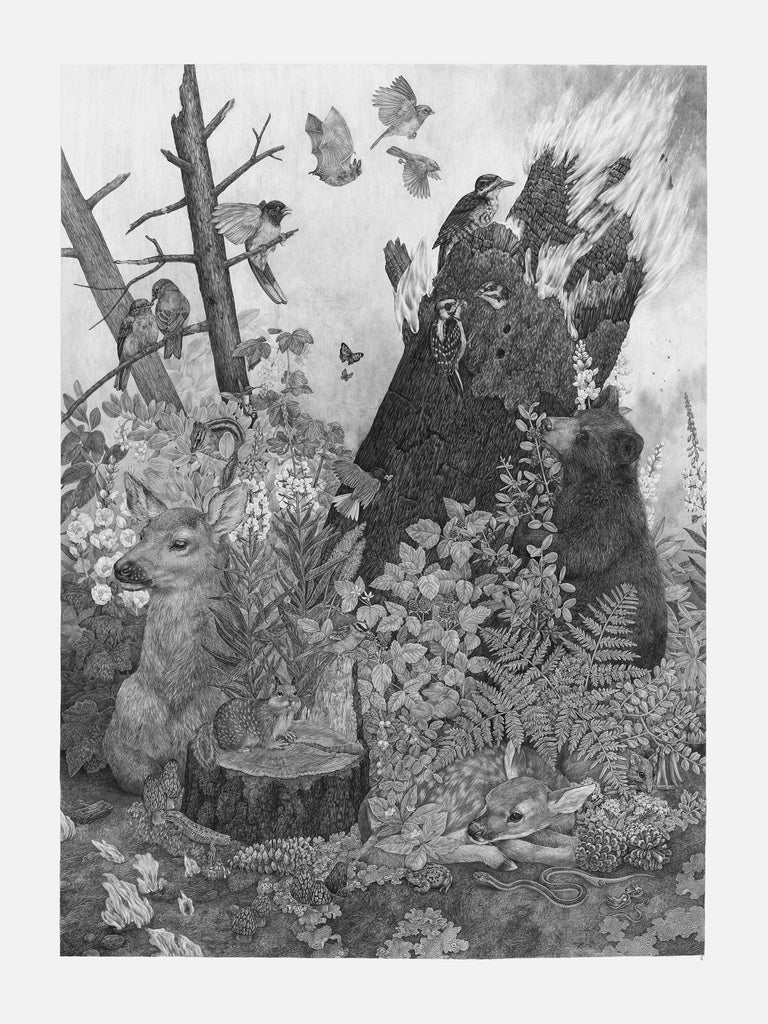

As a mixed or high severity fire sweeps across a forested landscape, it leaves behind the vital ingredients for the life of a new forest. Tree crowns burn, and some living trees are killed or damaged severely enough to die slowly in the following years. As these mature trees wane, the canopy is pulled open. Light rains down on the forest floor, nutrients and moisture once monopolized by trees becomes

available for new forms of plant life, and the ground is made rich with woody debris. Grasses, wildflowers, shrubs, and hardwood and coniferous tree seedlings take hold in this landscape, weaving together complex and diverse plant communities. This burst of vegetation creates habitats for a diverse group of species. Grasses, flower nectar, seeds and berries touch off a tangled food web, twisting through insects to rodents, birds, and bats, and finally to raptors like Northern Goshawks and Northern Spotted Owls that hunt from adjacent unburned forests. Larger mammals - Roosevelt Elk, Columbian black-tailed deer, and black bears in the Klamath-Siskiyou region - browse on foliage and berries. Equally as important as this lush new burst of greenery are the blackened ghosts of fires past, elements of the forest that are called “biological legacies.” Standing dead trees called snags, downed trees and woody debris provide unique habitats. Birds perch on the branches of snags, flying out across the opened landscape to feast on the flush of moths, butterflies and other insects. Bats dart across the sky, sharing in the six legged buffet. Woodpeckers dig grubs out of blackened trees, and excavate nesting holes that are used by succeeding cohorts of birds and small mammals. This vibrant stage in the life of a forest is called a “complex early seral forest,” a name applied to forests recovering from any type of disturbance, including not only fire but also wind, severe flood or volcanic eruption. This stage lasts until tree seedlings grow tall and the canopy closes once again, a process that can take decades or even a century. Because of their high levels of biodiveristy and relative rarity across forested landscapes of the Pacific Northwest, complex early seral forests are considered just as precious as old growth forests.

Zoe Keller - Postfire

$9,000.00

This product is sold out

Graphite on Paper, 60"x45”

This piece was created for Zoe Keller's 2018 feature show at Antler Gallery "Forest"

What is a Complex Early Seral Forest

As a mixed or high severity fire sweeps across a forested landscape, it leaves behind the vital ingredients for the life of a new forest. Tree crowns burn, and some living trees are killed or damaged severely enough to die slowly in the following years. As these mature trees wane, the canopy is pulled open. Light rains down on the forest floor, nutrients and moisture once monopolized by trees becomes

available for new forms of plant life, and the ground is made rich with woody debris. Grasses, wildflowers, shrubs, and hardwood and coniferous tree seedlings take hold in this landscape, weaving together complex and diverse plant communities. This burst of vegetation creates habitats for a diverse group of species. Grasses, flower nectar, seeds and berries touch off a tangled food web, twisting through insects to rodents, birds, and bats, and finally to raptors like Northern Goshawks and Northern Spotted Owls that hunt from adjacent unburned forests. Larger mammals - Roosevelt Elk, Columbian black-tailed deer, and black bears in the Klamath-Siskiyou region - browse on foliage and berries. Equally as important as this lush new burst of greenery are the blackened ghosts of fires past, elements of the forest that are called “biological legacies.” Standing dead trees called snags, downed trees and woody debris provide unique habitats. Birds perch on the branches of snags, flying out across the opened landscape to feast on the flush of moths, butterflies and other insects. Bats dart across the sky, sharing in the six legged buffet. Woodpeckers dig grubs out of blackened trees, and excavate nesting holes that are used by succeeding cohorts of birds and small mammals. This vibrant stage in the life of a forest is called a “complex early seral forest,” a name applied to forests recovering from any type of disturbance, including not only fire but also wind, severe flood or volcanic eruption. This stage lasts until tree seedlings grow tall and the canopy closes once again, a process that can take decades or even a century. Because of their high levels of biodiveristy and relative rarity across forested landscapes of the Pacific Northwest, complex early seral forests are considered just as precious as old growth forests.

Fire Regimes in the Klamath-Siskiyou Region

Fire has washed over the mountains of the Klamath Siskiyou for thousands of years, contributing to the region’s high level of biodiversity and shaping the region’s complex patchwork of forest types. Within a particular ecosystem the behavior of fire over an extended time scale can be described by a “fire regime,” a classification that points to the frequency, intensity and size of blazes in the ecosystem. In the Klamath-Siskiyou, fire-regimes are typically described as low to mixed-severity, occurring every five to every 35 years in drier vegetation and every 50 to 200 years in wetter and higher elevation areas. Low, or understory fire regimes, leave behind the majority of the dominant vegetation, doing little to change the structure of the ecosystem. Mixed-severity fire regimes are more complicated, but generally include a mixture of understory fires, crown fires that race along the upper branches of shrubs and trees and torching: when a single tree or small group of trees ignites and burns from bottom to top. Mixed-severity fires leave behind a puzzled landscape, with interlocking areas experiencing varying degrees of burning, sometimes over enormous areas. From July to November of 2002, the Biscuit Fire burned a mosaic across almost 500,000 acres (200,000 hectares) of mixed-evergreen forest. Biscuit was the largest blaze in Oregon’s history, and one of the largest in the modern history of the United States. The most dramatic fire regimes, called high severity or stand-replacing, torch the majority of dominant vegetation. Although their frequency is less understood, these fire regimes do occur in the Klamath Siskiyou region.